“Having searched for and already examined [new models of civilization], we now carry them out. Take broadaxes and long-handled swords to tear down the old wall; raise red flags and red banners in order to ascend the new stage; jump into the swirling world in order to agitate our enthusiasm; lead our enthusiasm into the forward-leaping time in order to encourage our incentives. It is essential to ensure that people in the country start competing on account of thoughts, and initiate thinking on account of competition, so that to some extent, through a series of works, will obtain the so-called studies for the advancement of civilization.”

(Anonymous, New Learning Strategies for the Advancement of Civilization, 1904)

Even though the definition of liberal arts may vary, they all refer to “a broad intellectual foundation for the tools to think critically, reason analytically and write clearly. These proficiencies will prepare students to navigate the world’s most complex issues, and address future innovations with unforeseen challenges.”(1) Historically, the philosophical foundation and practice of such education traditions has long existed not only in the West, but also in non-Western countries such as India, China, and Egypt.(2) The establishment of Quốc Tử Giám (“the Imperial Academy”) in 1076 can be considered an important milestone that ushered in liberal educational traditions in Vietnam. Here, the meaning of “liberal” must be understood in the historical context of a nation that, in the 11th century, “had just re-gained its autonomy after 1,000 years of foreign colonization”, whose “keen sense of preserving and consolidating its independence, and asserting its fortitude” playing the role of “the leading thought for all administrative, military and cultural activities devoted to the task of nation-building.”(3) More than 830 years later, during the French colonial time, another school was born, marking a new development in the liberal educational traditions in Vietnam.

Founded in 1907 in Hanoi, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục (“The Tonkin Free School”) was a synthesis of the achievements in Eastern and Western education reforms in the late 19th – early 20th centuries, to respond to the pressing demands of the time, especially to the all-encompassing need of reforming the country in pursuing progress, equality, collaboration, and national sovereignty. The epigraph to this article is an extract from Văn Minh Tân Học Sách (“New Learning Strategies for the Advancement of Civilization”), often considered the school’s manifesto – creed – and compass, clearly articulating the spirit of critical and liberal thinking, and the desire for national development that can keep a balance between local and global interests. The short span of its existence, approximately 10 months, stands in inverse proportion to the school’s far-reaching influence on the liberal educational traditions in Vietnam in particular, and on the development of Vietnamese society in a new direction in general.

A brief overview of historical contexts

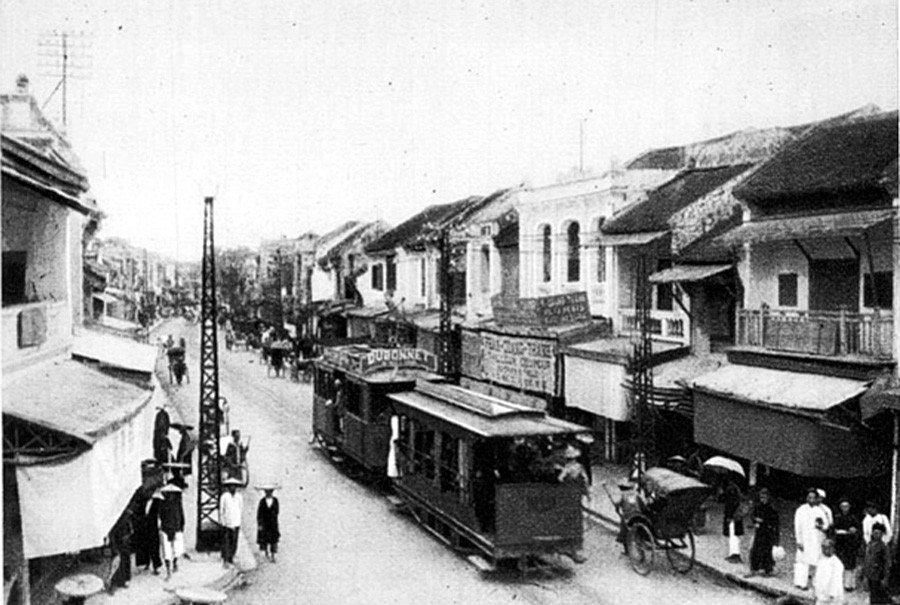

Political, economic, social and military upheavals in the East Asian region during the late 19th – early 20th centuries had a major impact on Vietnam – a country that was divided into Northern, Central, and Southern territories under French colonial rule and its protectorate political systems. The failure of the Wuxu Reform in 1898 in China had forced Kang Youwei (1858-1927) and Liang Qichao (1873-1929) into exile in Japan, and that could be regarded as a crucial starting point for a series of events that enabled the spread of Western political and philosophical thoughts throughout East Asia, including Vietnam, in the form of “tân thư” (literally, “New books”). The victory of Japan in the Russo-Japanese War (1905), along with its achievements in political, economic, educational, and social reforms during the Meiji Restoration period (1868-1889), prompted the other East Asian countries to reassess their own potentialities for revolution and reform in order to push back the threat of annexation from the West. The people’s knowledge, national spirit, and well-being thus arrived on the scene as fundamental factors for the country’s path towards national self-reliance and modernization, which called for special attention and required specific actions, starting from the educational front. The education model of Japan, specifically the Keio Gijuku school, to which Phan Bội Châu (1867-1940) and Phan Châu Trinh (1872-1940) paid their visit in 1906, became a source of inspiration for the establishment of the Tonkin Free School on Hàng Đào street, Hanoi, under the stewardship of Confucian literatus Lương Văn Can (1854-1927).

From left to right: No.4 (Lương Văn Can’s private residence, far right) and No.10 (the white building with three arched windows) on Hàng Đào street, served as the bases for the Tonkin Free School’s teaching activities. Source: Henri Gourdon, L’Indochine, Paris: Larousse, 1931, p. 131.

The Tonkin Free School – A crucial stepping stone in the history of education in Vietnam

Despite its brief 10-month existence, from March 1907 to early 1908, when it was quashed by the colonial regime,(4) the Tonkin Free School was one of the most significant reforms in the history of education in Vietnam, carried out not through a top-down, but a bottom-up execution triggered by the will of the people, incited by intelligentsia and their aspiration for national sovereignty, their patriotism, and their appeal for progress in the realm of knowledge, thought, and democracy in order to tear down constraints and stagnation deep-seated in Vietnam’s monarchical and colonized society of the early 20th century. The primary reason that prompted the French regime to put down the Tonkin Free School wasn’t due to its progressive curriculum on sciences, but more importantly, it was due to the risk of combining the training of new people with scientific thinking, open-but-critical mind, deeply patriotic, consciously striving for the attainment of the world’s knowledge, yet invariably aiming for national sovereignty with armed uprisings, which could break out across the country at any given moment.

Reconstructing an educational reform prohibited by the colonial regime

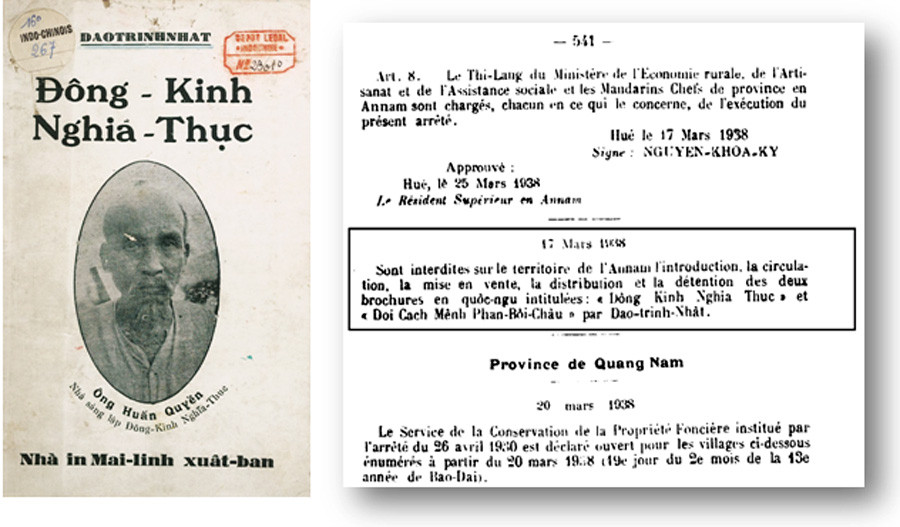

There remains a yawning chasm between the time when the Tonkin Free School operated and the time when the first research on this school was publicized. After its suspension, not until 30 years later did the earliest monographs on the school emerge, and yet, their fate also suffered from endurances. The book Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục (“The Tonkin Free School”) by Đào Trinh Nhất (1900-1951), printed by the publishing house Mai Lĩnh in December 1937 in Hanoi with a sizable amount of 10,000 copies, was swiftly banned, along with other work by the same author, titled Đời cách mệnh Phan Bội Châu (“The revolutionary life of Phan Bội Châu”). The ban dictated that starting from March 17, 1938, no one were allowed to “introduce, circulate, sell or distribute” these books all over Annam.(5) Concurrently, since 1936, Hoa Bằng Hoàng Thúc Trâm (1902-1977) had gathered information on the Tonkin Free School and sporadically relayed them to readers of the weekly newspapers Thế Giới (“The World”, Saigon) and Tân Việt Nam (“New Vietnam”, Hanoi). In 1945, with sufficient materials at hand, he began composing the book Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục (“The Tonkin Free School”) under the pen name of Mai Lâm, but the tumult of war had caused the loss of this manuscript. Not until ten years later could Hoa Bằng finish yet another manuscript on this historic school, unfortunately, up until now, it hasn’t seen the light of day.(6) For a protracted period of time, the name “Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục” had become a taboo that haunted the colonial regime since 1908, when it was labeled “hội kín” (société secrete/secret society) and associated with riotous revolutionary activities, such as the poisoning case of French soldiers in Hanoi within the same year.(7)

Left: The cover of Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục by Đào Trinh Nhất, published by Mai Lĩnh in 1937, featuring the portrait of the school’s principal Nguyễn Quyền; Right: The article that banned the two books Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục and Đời cách mệnh Phan Bội Châu, was issued on 17 March 1938 in the Bulletin administratif de l’Annam, 1938/ 02/15-1938/ 08/09. Source: Gallica, The Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The Tonkin Free School through oral history

Aside from some brief reports on the school printed in the daily newspaper Đại Nam đồng văn nhật báo/Đăng cổ tùng báo in 1907 while the school was still active, the two monographs penned by Đào Trinh Nhất (1937) and Nguyễn Hiến Lê (first published in 1965, reprinted in 1968), judged by their nature, were oral histories composed in later times. Đào Trinh Nhất’s book came out as the result of “hours of conversation with the founder of the Tonkin Free School”, a history orally relayed to the author by Nguyễn Quyền (1869-1941), the school’s former principal who, at the time, was placed under house arrest in Bến Tre by the colonial regime. In his 1955 prologue, Nguyễn Hiến Lê acknowledged his fortune of “being a direct descendant of a Confucian scholar who advocated for the Free School, oftentimes listening to his recollections of the school’s history (…),” and emphasized the fact that “this modest book in your hands is not a history book, but merely a book containing historical materials.”(8) Although he never referred to the concept of “oral history” in his work, Nguyễn Hiến Lê also offered some points worth noting regarding the verisimilitude of this type of historical documentation: first, the subjectivity of the narrator; second, the credibility of memory; and finally, the limitations to verify facts and stories being told.(9)

The Tonkin Free School’s liberal education

If, despite the passage of time, what remains indelibly imprinted on one’s mind was the most cherished of memories, then the things that former principal Nguyễn Quyền could still recall 30 years later after the colonial regime revoked the Tonkin Free School’s license and arrested, banished, or imprisoned its founding members, must have been of the school’s proudest achievements. He summed up the school’s pedagogic principles and missions as follows.

1. Classes were conducted in French, Sino-Vietnamese, and Vietnamese: For general education, the emphasis should be placed on the teaching of Vietnamese script and vernacular literature, completely replacing classical Chinese with the Romanized national script to “deliver general knowledge and new ideas.”

2. The school was divided into three levels: primary, high school, and higher education. French and Sino-Vietnamese were taught at both high school and higher education levels. The school accepted both male and female students for primary education; its faculty also included female teachers. All classes were structured around the fundamental principles of “learning how to become a citizen, instead of inculcating the well-trodden practices set by the Imperial civil service examination.”

3. The school provided free education for all, which entailed free allotments of books, school stationaries to students, so that “anyone can simply come and afford an education”.

4. The school taught “the general knowledge of sciences and technology, which shall serve as a basis for one’s own sustenance of life and work.”

5. Given the ruling government’s green light, the Tonkin Free School shall, on a weekly basis, deliver public lectures on educational and scientific matters; originally confined to Hanoi, the school later dispatched its speakers to other regions to deliver its public lectures.

6. The Tonkin Free School by its nature was experimental, serving as preparations for future’s duplication of its education model across the three regions of Vietnam.(10)

The anonymously penned Văn Minh Tân Học Sách (“New Learning Strategies for the Advancement of Civilization”) can be considered the Tonkin Free School’s educational creed. Here, the school opted for encouraging the spirit of scientific innovation in learners, urging society to follow the exemplar set by European countries and “issue a national decree wherein any person who demonstrates his mastery of the new knowledge, who successfully invent new things, shall be, following European traditions, accorded a certificate of merit, bestowed titles, and entitled to an allowance as a reward, so that they can retain the right to innovate.” Most importantly, the school placed emphasis on the spirit of academic freedom based on practical learning, “enabling students to engage in unfettered discussion, open dialogue, without the slightest hesitation. Formal stricture should prove itself unnecessary (…) in the alignment between what the students learn in school and the practicalities of their everyday life”.(11)

Naturally, the Tonkin Free School’s curriculum could not reach maturity during its brief 10-month existence, yet the boldness of its founding members in abandoning the well-trodden practices set by the Imperial Examination and Confucian classics, the oppressive dogmas and constraints imposed on the people’s mind for thousands of years, should be recognized as an important milestone in the history of education in Vietnam. It was that very spirit of liberal education which allowed learners to bask in the light of academic freedom, steering them towards the path of practical learning, enabling them to verify for themselves what they had learned in school, to exercise their faculty for open thinking and critical reasoning, without any inhibitions nor hesitancy. Alongside the Vietnamese national script, Classical Chinese and French still served as complementary languages – literature that allowed learners to broaden their knowledge and effectively accommodate himself to the modern world, without severing the roots of his motherland. The Tonkin Free School, as such, had carried on and promoted Vietnam’s liberal educational traditions within the framework of colonialism, amid a world caught itself in the intricacies and turmoil of the early 20th century.

Dr. Nguyen Nam, Director of Vietnam Studies Center, Fulbright University Vietnam

______

1. Harvard College, “What is a ‘liberal arts & sciences’ education?”, accessed 23 February 2022.

2. Kara A. Godwin and Philip G. Altbach, “A Historical and Global Perspective on Liberal Arts Education: What Was, What Is, and What Will Be,” International Journal of Chinese Education,5 (2016), pp. 9-11.

3. Đỗ Văn Hỷ, Quốc tử giám và Trí tuệ Việt, Hà Nội: Thanh niên, 1995, p. 8.

4. According to Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục by Nguyễn Hiến Lê (second edition, Sài Gòn: Lá Bối, 1968), while waiting for the permit from the colonial government who was still cautious and hesitant about the school’s purpose and mission, around March 1907, the founding members of the Tonkin Free School began organizing two classes at No. 4 Hàng Đào street. Two months later, in May 1907, the school officially received their permit. Early 1908, the French colonial government revoked the school’s permit. (pp.. 48, 49, and 115).

5. Bulletin administratif de l’Annam, 1938/ 02/15-1938/ 08/09, p. 541.

6. In his review of the Tonkin Free School in Lịch sử Tám mươi năm chống Pháp (Volume I, Hà Nội: Ban Nghiên cứu Văn Sử Địa, 1956), Trần Huy Liệu writes “Part of the materials in this chapter is drawn from the unpublished book Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục by Mai Lâm.” (p. 142, endnote no.3)

7. Pierre Tedral, La France devant le Pacifique. La Comédie Indochinoise, Paris: Aux Éditions Vox, 1926, p. 50.

8. Nguyễn Hiến Lê, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục, the “Preface” of the first edition (unnumbered).

9. Ibid.

10. Đào Trinh Nhất, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục, Hà Nội: Mai Lĩnh, 1937, pp. 22-23.

11. Nguyễn Hiến Lê, Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục, pp. 52-53.